It's now Day 23 of my April blog posts about the writing of Before Beltane.

Today's post is about basic necessities. There are a few absolute basic necessities to sustain life and it depends very much on circumstances if a person ever actually gets to a point where they find themselves faced with sourcing basic things to keep them alive. Today, it depends on where in the world you live that you may face this life or death situation more often than others. If a person lives in a drought area of high temperatures, they may face starvation not because of the will of the locals around them to work, it may just be that forces of nature - excoriating heat levels and lack of water - are beyond their control. In other cases, it may be war that makes basic life a day-to-day experience.

In Before Beltane, Nara finds herself cast adrift. She can no longer live at the priestess nemeton home on the Lochan of the Priestesses. Instead, she is given the most basic of shelters at the hillfort of Tarras, though her father Callan, chief of the hillfort, would rather she be banished altogether. The roundhouse is dilapidated and has been abandoned for some time. It is entirely bare inside, so she must find ways of keeping herself alive since Callan has ordered everyone at the hillfort to shun her. They must not help her, or they will face severe punishment.

The most basic needs of life are shelter; water and food. Though distraught over her situation, Nara knows what she must do...

Here is a small excerpt from Before Beltane:

Fending for herself meant

collecting fresh water, a brief forage for food, and a swift gathering of

firewood. There was a spring-fed well in the hillfort, but she had no intention

of being turned away from it. She would not give her father that satisfaction.

She knew where the nearest

spring-fed burn was situated, only a few copses away, so she made

water-gathering her first task. As she passed through a hazel grove to get to

the burn, she collected the few nuts that she could find still littered under

the decayed leaf fall and popped them into her sack. From the dearth of nuts

lying around, she could tell that others had been successful in seeking them

moons ago, and not just the squirrels in preparation for the long sleep of

winter that they were now awakening from.

On reaching the burn, she paused

to pay homage.

“I come in great need, Coventina

of the spring. Accept my humble thanks for your life-giving waters.”

Unable to donate any of her

personal items, she added a pledge to do better on her next visit then bent to

fill her water skin. She tied it tightly at the neck and attached it to her

belt, knowing from the growing dimness around her that time for her tasks was

scarce.

One good thing she knew about

dusk was that the small creatures of the forest tended to rise from their rest

to look for their own food. Pulling her sling free from her leather pouch, she

looped it over her left wrist and fisted some sling-stones, thankful that she

always maintained a good supply. Though having a few at the ready did not mean

she could throw caution to the winds. The animals of the forest did not make

the hunt easy, and nor should they. She would have fed off some oats if she had

them, rather than unnecessarily kill any of the small creatures, though it was

unlikely she would be having a share of the Tarras cereal crops.

The scurrying of a squirrel

descending from one of the oaks ahead set in motion the perfect hunting

conditions. Her spear flew from her fist, but shockingly it fell far short of

the target. How that had transpired was mystifying; her aim was never normally

so poor. She looked down at her hand. It was trembling. And must have been

trembling before she fired the spear, though she had been unaware of it.

“Andraste? Have you also

deserted me?”

Flurries of the littlest brown

birds rose into the upper branches on hearing her wail, but it was one of the

slightly bigger ones that she kept in her sight as it tapped away at gnarled

old oak trunk. The startlingly coloured feathers striped black and white, with

a red underside, meant only a small feast would be had from that type of

tree-pecking bird, though it would suffice till the new dawn. Sidestepping very

slowly, she concealed herself behind a gnarly-trunked holly tree.

The whirling of her first sling

stone only served to warn the bird enough for it to fly off to a nearby rowan,

not its preferred place as far as Nara had observed when hunting. Affixing a

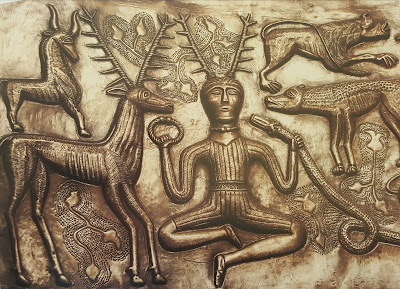

second stone as silently as she could to her sling, she sent a silent plea to Cernunnos

to afford her one small kill. Without unnecessary movement, she sidled around

the trunk and let it fly. This time it made its mark and the bird plummeted to

the ground from the rowan that was still leaf-free.

Bowing her head over the dead

bird when she reached it, she gave thanks to the forest god. “My thanks to you Cernunnos,

lord of all the creatures within your domain. I appreciate your bounty. Know

that I only kill to survive another day.”

The bird carcass was added to

the collection that hung from her belt before she began the task of retrieving

her spear.

On the way back to the forest

fringes, one by one she plucked up an armful of longer branches and dragged a

few even heavier ones behind her. The routine task kept only some of Nara’s swamping

thoughts at bay. What mostly filled her mind was what she needed to do to

continue to survive her dreadful situation.

Near the edge of the forest she

dumped her pile on the ground, removed her short cloak and opened it out.

Yanking out her long knife, she hacked at the branches to make them a tidier

pile for carrying, and set them onto the opened material. Her last gathering up

was of smaller twigs; mosses to dry for tinder; and long dried brackens to make

a torch.

When the pile was as much as she

could reasonably manage, she bound it up tightly with grass twine from her

pouch and swung it up onto her shoulder, bracing her arm around it to balance

the weight. She plucked up her spear from where it was propped against a bush,

dipped her chin and closed her eyes.

“My thanks to you Cernunnos,

lord of the forest. I promise I will use your gifts wisely.”

By the time she was out of the

trees, darkness had fallen and the clear dark blue above was being replaced by

a deeper bluish-black. Her trek back to Tarras was lit by the goddess Arianrhod,

her full silver globe having replaced the yellow disc of Bel.

Nara sighed and awkwardly shifted her burden to

her other shoulder, her spear transferring from hand to hand, when the looming

presence of the outer ramparts of Tarras came into sight. Few visitors, or

tribespeople, entered through the outer defence ramparts at night. She guessed

that her arrival would not be a welcome one, but prayed to her favourite

goddess Rhianna that she would be given some clemency – especially if it

was the hostile Afagddu who was still at the gate.

You can Pre-order Before Beltane eBook

HERE

Or buy a Before Beltane paperback HERE

Happy Reading.

Slàinte!

_-_n._11141_-_Museo_di_Napoli_-_Strumenti_di_chirurgia.jpg)

_(14566397697).jpg)

_(7685208580)_2.jpg)